© 2025 Puja Goyal

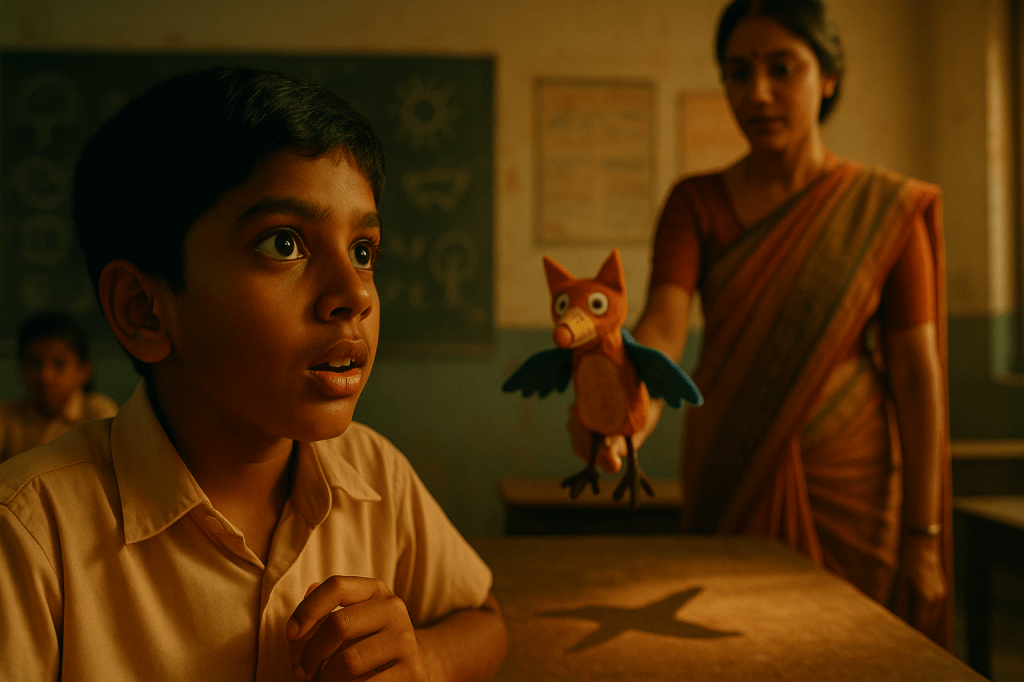

Jitty was about to hurl his pencil across the room when the teacher whispered, “…and that’s when the fox, trapped in a cage of fire, looked straight into the hunter’s eyes—and smiled.”

The pencil paused mid-air.

A breath was held. Not just his.

Somewhere, a story had cracked the spell of boredom, like sun through a monsoon cloud. The room shifted. Desks became forest floor. The fan hummed like crickets.

This is not magic. This is storytelling. And it’s how children begin to learn—when they feel first.

Too often, we think of stories as dessert—something sweet to end the day. But story is not dessert. It is the plate. The fork. Sometimes, even the meal itself.

Because before a child memorizes the periodic table, they must learn to care why anything changes at all. Before they understand the freedom struggle, they must feel what it means to long for freedom. And before they can solve for X, they must want to solve something real.

Story invites that want.

But let’s be clear: storytelling is not just the act of “once upon a time.” It’s articulation. Rhythm. Attention. The ability to take a foggy idea and give it legs and lungs and a heartbeat.

Teachers—when you explain a math problem with the urgency of a mystery novel, when your voice drops before revealing a historical twist, when you let silence sit long enough for a question to land—you’re not just imparting information. You’re giving language a pulse.

Here’s something you already know but might have forgotten: children don’t remember what you said, but they remember how you made them feel about learning it.

In a school in Baroda, a science teacher once turned photosynthesis into a courtroom drama—chlorophyll on trial for “stealing” sunlight. Engagement shot up. Kids who had never raised a hand began arguing on behalf of the stomata.

In a classroom in Bangalore, a teacher framed every grammar rule as a spell—“Subject-Verb Agreement” became a Hogwarts-worthy chant. Even the shyest child recited with theatrical flourish.

These aren’t gimmicks. They’re ways to honour the emotional architecture of learning. Because when a child feels something—delight, suspense, empathy—the information rides on that current straight into long-term memory.

And it’s not just children. Story is how we all make meaning of the world. Professionals who present data without narrative lose their audience. Leaders who speak without metaphor rarely inspire. Parents who explain without analogy often repeat themselves.

So if you teach, lead, explain, or speak—storytelling isn’t a skill you might explore. It’s the skill you already use, and can sharpen with intent.

This week, notice how you speak. Where does your voice rise? When do eyes light up? What metaphors do you reach for?

And ask yourself, gently: am I trying to be understood, or remembered?

Because when you speak to the heart, the mind follows.

And sometimes—just sometimes—a child doesn’t throw the pencil.

Coming Soon: The Storytelling Classroom—a professional development workshop by DreamScope Theatre, designed for educators, facilitators, and communicators seeking to elevate their teaching through the art of storytelling.

Because the future of education begins with how we speak, listen, and connect.

Leave a comment